Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s sandbox, from those who inspired him to those who were inspired in turn.

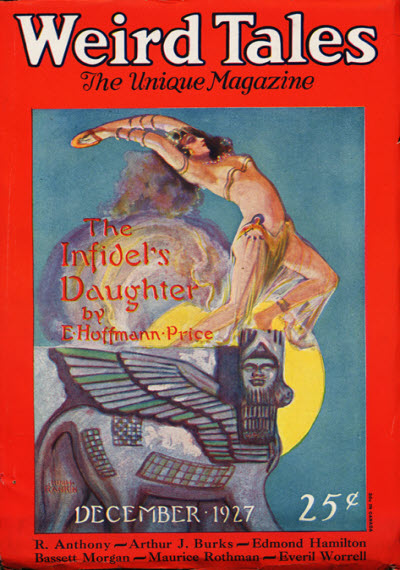

This week, we’re reading Everill Worrel’s “The Canal,” first published in the December 1927 issue of Weird Tales. And, um, accidentally also August Derleth’s 1947 revision, first published in his The Sleeping and the Dead anthology. Spoilers ahead.

Narrator Morton has always had “a taste for nocturnal prowling.” Most people roam at night only in well-lit “herds”; Morton now understands how dangerous it is to be different. Those who read his last missive will call him a madman and murderer. If they knew the sort of beings from which he’s saving the city, they’d call him a hero.

Morton, just started on his first post-college job, accepts an invitation to weekend at office-mate Barrett’s tent camp across the river. The camp bores him, but the boat trip reveals a more promising destination. On the city side of the river is a “lonely, low-lying waste” of hovels and scattered trees, bisected by a disused canal and tow-path.

Monday, near midnight, Morton crosses a foot-bridge to the tow-path. He walks upstream, leaving behind the shacks for pleasingly desolate woodland. Then dread strikes; as he’s “always been drawn to those things which make men fear,” Morton’s new to the prickle that courses his spine. Someone’s watching.

Peering around, he dimly discerns an old barge half-sunk in the canal. On its cabin perches a white-clad figure with a pale, heart-shaped face and gleaming eyes. It’s a girl surely, but why here? Morton inquires whether she’s lost.

The girl’s whisper carries clearly. She’s lonely but not lost—she lives here. Her father’s below decks, but he’s deaf and sleeps soundly. Morton can talk awhile if he likes. Morton does like, though something in the girl’s tone both repulses and powerfully attracts him. He wants to lose himself in her bright eyes, to embrace and kiss her.

He asks if he may wade over to the canal-boat. No, he must not. May he come back tomorrow? No, never in the daytime! She sleeps then, while her father watches. They’re always on guard, for the city’s gravely misused them.

How painfully thin the girl is, how ragged her clothes, and how Morton pities her. Can he help her with money or in getting a job? But rather than give up her freedom, the girl would prefer even a grave for her home!

Buy the Book

The Monster of Elendhaven

Her spirited outburst strikes a responsive chord in Morton. Overcome by the romance of it all, he swears to do whatever she commands. In turn, she tells hims that she’ll come to him when the canal ceases to flow, and hold him to that promise. The canal’s moving slower all the time; when it’s stagnant, she’ll cross.

Morton feels the cold wind again and smells unwholesome decay. He hurries home, but returns nightly to the stranded girl. She speaks little; he’s content to watch her until dawn, when fear drives him away. One night she confesses her and her father’s persecution was at the hands of the down-river hovel dwellers, who reviled and cursed her. Morton doesn’t like to associate his “lady of darkness” with the sordid shacks. At the office, he asks Barrett about the canal-side community. Barrett warns it’s been the scene of several murders. It was in all the papers how a girl and her father were accused of killing a child—later found in the girl’s room, throat mutilated. Father and daughter disappeared.

Morton remembers that horror now. Who and what is the girl he loves? He muses on stories of women who succumb to bloodlust in life, then retain it in death, returning as vampires who drain the living with their “kiss.” Such creatures have one limitation—they can’t cross running water.

He returns to the now-stagnant canal. In flashes of heat-lightning, he sees a plank stretched between barge and canal bank. Suddenly she’s beside him, and while he longs for her touch, “all that [is] wholesome in [his] perverted nature [rises] uppermost,” making him struggle against her grasp. Realizing his love has turned to dread, the girl hates him. He thus escapes her kiss but not his oath. She hasn’t waited months only to return to her barge-prison. Tonight he must do her will.

Which is to carry her over the river bridge to the camp on the opposite shore. Morton does so, loathing, through a tempestuous thunderstorm. She directs him to an old quarry, orders him to shift a stone from a crevice. The heavy slab strikes him as it falls, but he still sees the bats squirming from the opening—bats the size of humans! They fly toward the campground. Morton staggers after.

The bats, he realizes, have entered the tents to feast on the campers. One web-winged silhouette turns into his beloved, begging for shelter from the storm. Morton tries to warn the couple inside that she’s a vampire—they’re all vampires!—but the girl convinces her victims-to-be he’s mad.

Morton flees back to the city. By daylight he finds the father in the barge, a well-rotted corpse. No wonder the girl wouldn’t let him board, even to carry her away. Soon after he learns that the campers were attacked by rats that bit their throats. He’s already sworn to die before yielding to his compulsion again; now he decides to dynamite the vampires’ quarry lair and the infected campground. After that, he’ll throw himself into the black canal water, midway between the shacks and the barge. This can be his only peace—or if not peace, at least expiation.

What’s Cyclopean: The clouds have a “lurid phosphorescence,” and that’s before the deeply atmospheric storm kicks off amid the “miasmic odors of the night.”

The Degenerate Dutch: Those houses on the wrong side of town: you just know they’re full of murder.

Mythos Making: A narrator who prefers morbidity and solitude to the company of ordinary men discovers the things that lurk outside the tenuous protection of civilization.

Libronomicon: Poe comparisons abound, but it’s vague memories of Dracula that get Morton up to speed on his nemesis.

Madness Takes Its Toll: He shall be called mad. Let the things he writes be taken for the last ravings of a madman. It would take very little for the office force to decide he was mad. Madness overcomes him, in the madness of his terror. Trees lash their branches madly, much like clouds careen. You will call this the ravings of a madman overtaken by his madness. He runs away, madly—as a soon-to-be-vampirized couple describe him as crazy, out of his senses, and crazed.

Anne’s Commentary

I first read “The Canal” a dozen years ago, in an anthology of pulp-era stories called Weird Vampire Tales, edited by Robert Weinberg, Stefan Dziemianowicz and Martin Greenberg. Its urban-fringes setting immediately pulled me in—like Morton, I was always drawn to those scruffy borderlands between concentrated (and more or less orderly) mankind and the wild (or what passes for it around concentrated mankind.) A canal ran through my neighborhood in Troy, New York, to debouch into the mighty Hudson River. In spring it flooded, and herring leapt upstream over its miniature cataracts, flashes of flailing silver. At less hectic times of year, I could wade among its rocks. There was also a thickly wooded island in the Hudson perfect for night prowls; it was particularly adventurous to go there, since minus a boat one had to halfway cross a major bridge, then clamber down to the island via its underpinnings. I never met any vampires there, though there were some deserted shacks and the occasional bonfires of teenage “cultists.”

So I was excited to read “Canal” again, and the nostalgic revisit was going fine until the end of the story. Wait, what? Morton hauls Vampire Girl all the way over the bridge just so she can cheat on him with some anonymous camper dude while he mopes under a “gibbous” moon that was in the dark phase a few paragraphs back? And what was this about a war-slain uncle and a wooden toy sword? Which Morton was going to slay Vampire Girl with, after he got her Kiss? As if she who had telepathically divined his every thought would miss the one reading “I’m about to run you through with my little oak sword, you bewitching bitch!”

First, that reminds me of how Susan in King’s ’Salem’s Lot pulls a slat from a snow fence just in case she has to off a vampire. Because that would work. Luckily she meets Mark Petrie, who’s brought a heavy ashwood stake and hammer.

More pertinently, I didn’t remember this ending. Hadn’t there been a whole bunch of vampires awaiting their magical release at Morton’s human hand? Hadn’t they descended on the tent camp for a nice midnight picnic? Could I really be thinking of another story that closed with such awesomeness after a similar build-up of boy-meets-barge-girl-along-midnight-canal, unholy-obsession-ensuing?

It didn’t seem likely.

And it turns out the link I followed to Wikisource from our blog was NOT the story I’d originally read, which I verified by going back to my Weird Vampire Tales anthology. Huh. Did Worrell write two versions? If so, which was the first version, and why a revision? Some online sleuthing later, including an enjoyable listen to Chad Fifer and Chris Lackey’s H. P. Lovecraft Literary Podcast on “Canal,” I had an answer. The “Canal” Worrell wrote (and which Lovecraft named one of his favorites for cosmic horror and macabre convincingness) was the 1927 Weird Tales version. Now, Weird Vampire Tales reprinted the 1927 “Canal.” Whereas the Wikisource “Canal” is an August Derleth revision, which he included in his 1947 anthology The Sleeping and the Dead.

I mean, WTF?

Have to admit, I haven’t dug deeper into why Derleth thought he should revise Worrell’s work. Or whether she authorized the revision. Or whether he acknowledged revising “Canal” for his anthology. Without which information I don’t want to comment further on the situation other than again, WTF? Derleth’s version left me sadly disappointed in my old favorite. If you want to argue it weakens “Canal”’s perverse romance to suddenly dump in an economy-size boxload of giant bat-vamps, I think you can effectively do so. If you want to question whether the dynamite-fueled climax isn’t an action-movie trope too far for its atmospheric tone, could be something in that. But if these are Derleth’s arguments, he doesn’t validate them through his changes. Rather the opposite—I was happier with the giant bats and dynamite after reading the “remake.”

And I love me some perverse vampire romance. And am not a huge advocate of solving problems (fictional or real) by blowing them up real good.

Anyway, investigating the Case of the Two Canals has given me the bonus of reading more about Everil Worrell. She was one of these charmingly annoying fantasists who travelled much and wore many hats in addition to writing: painter, singer, violinist, long-time employee of the U.S. Treasury Department. She was also a steady contributor to Weird Tales, with nineteen stories published between 1926 and 1954 (one under the alias Lireve Monet.) Now that I’ve bumbled into the online WT archives, I’ll be reading more of Worrell!

A final squee. Somehow despite enthusiastically following Night Gallery, I managed to miss its “Canal” adaptation, renamed “Death on a Barge” and directed by Leonard Nimoy, no less! I shall soon remedy that, and you can too!

Ruthanna’s Commentary

What makes a vampire story Weird? Certainly bloodsucking fiends of the night aren’t inherently weird (unlike, say, squid). I’m not even talking Twilight here—lots of vampires are either inherently civilized creatures (you can’t eat the aristocracy if they eat you first) or one of the monsters that define the safe bounds of civilization—stay inside the lines, and you’ll be fine. In the weirdest fiction, those lines meet at angles and reality creeps in anyway. Worrell’s vampires have some of this safety-defining nature: Morton bemoans his gothy nature, certain that if he enjoyed well-lit parties instead of solitary graveyard strolls, he’d still be happily ignorant. It’s civilized habit, he tells us, that allows most people to live free of both terror and vampires.

On the other hand, one of my private subgenre definitions is that the more Weird a story is, the easier it is to fill in our trackers for things that are cyclopean, places where madness takes its toll, etc. Worrell’s story provides vivid descriptions in abundance, more atmospheric madness than I could count, and a narrator who’d get along famously with many of Lovecraft’s narrators assuming he cared to strike up a conversation in the first place. I do wonder how much of Weird Tales was simply a promise to the reader that if you kept being thoroughly goth, eventually you’d earn—and regret—a story of your very own.

Also prototypically weird is the Last Explanation That You Won’t Believe. Morton’s making a great sacrifice, and committing an apparent atrocity, all to save the people who stay safely in the light. And though he claims not to care if he’s considered delusional, he does leave the explanation. We’ve had plenty of final diaries, scrawled screams cut off by hounds and giant deep ones. The desperation to be understood, and the likely impossibility of understanding, might strike a chord even in readers who don’t spend their sleep-deprived nights wandering along dying canals.

All of which is undermined by Derleth’s bowdlerized ending. August Derleth, perennial problematic least-fave—who helped preserve and spread Lovecraft’s work, who undermined others’ efforts to do the same, who tried to fit the Mythos neatly into a dualistic Christian worldview, and who in general seems to have had all the story-sense of the lowest-risk Hollywood executive in existence. Here he is again, cutting Worrell’s disturbing ending in favor of a sexualized scene in which a man must destroy the woman he loves because she’s a monster—but gets a final embrace out of the bargain. Totally original, dude. I’m sure Everil would have written it just exactly that way, if only she’d thought of it.

Why would Derleth pull this crap, aside from the need to get his greasy fingerprints all over everyone else’s work? Maybe he was a little… uncomfortable… with Worrell’s own firm independence. Morton’s real point of no return, after all, isn’t walking dark, deserted paths. It’s spotting a pretty face in the darkness and making an unbreakable chivalric oath on the strength of a moment’s acquaintance. The Lady may be a blood-sucking fiend of the night, but her horror at the cage of a man’s “protection” seems like the sort of passionate declaration that a lot of women could get behind. Morton’s “romantic” urges require no awareness of her personality and interests—and the way they go stunningly wrong doesn’t offer the least bit of sensual reward. It’s at least a touch of fantasy: Wouldn’t it be satisfying, if the men who treat you like a blank-slate object for affection discovered just how dangerous it is to make such assumptions? No wonder Derleth couldn’t leave it alone. (It wouldn’t work, either. She reads minds. Idiot.)

Next week, we begin what will probably be an irregular exploration of Other Stuff By Lovecraft Collaborators with Sonia H. Greene’s “Four O’Clock.”

Ruthanna Emrys is the author of the Innsmouth Legacy series, including Winter Tide and Deep Roots. Her short story collection, Imperfect Commentaries, is now available from Lethe Press. You can find some of her fiction, neo-Lovecraftian and otherwise, on Tor.com, most recently “The Word of Flesh and Soul.” Ruthanna is online on Twitter and Patreon, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.

Thanks to procrastinating, I was spared the Derlethed version. I’m rather glad. The original is definitely worth a read. There were several little hooks that felt quite connected to Lovecraft. The narrator’s nocturnal habits most strongly reminded me of “He” (I think; that’s the one where the guy wanders the back streets of NYC and has some weird time travel stuff happen to him?) plus the whole general “They will think I’m mad” business. Other parts made me think of “Call of Cthulhu’s” opinion that blissful ignorance is the most merciful thing in the world. It never really rises beyond an ordinary vampire tale, though. All right giant bats eating campers and the hero dynamiting their cave is a bit beyond ordinary, but there’s no cosmic horror.

That Night Gallery episode Anne mentions was not only directed by Leonard Nimoy, it was his first directing gig. And it stars Lesley Ann Warren as the vampire (named, for some reason, Hyacinth; a name which carries very different connotations for me).

There’s a bit of a biography of Worrell here.

To answer the question of the title, is there such a thing as too goth? I’d personally say unleashing giant vampire bats crosses the line.

So nice to see a shout-out to Chris and Chad, long may they ‘cast.

Like gilding the lily or overegging the pudding, you can have too much goth. If it starts to pull you out of immersion, it’s being used too heavily.

I was hoping to see some nice, unconvincing, giant bats, but the Night Gallery episode seems to be based on the other version of this story.

I read this one back in February, when the SFFAudio Podcast covered it. I then tracked down the ‘Night Gallery’ interpretation. Leslie Ann Warren convincingly plays a vamp who could drive a lonely sort to do something inadvisable.

The thing that strikes me about the ending is the narrator’s compulsion to kill himself in expiation… I think a modern take would have him go on to become an itinerant monster slayer after what he unleashed on the community.

No, there is no such thing. I want all the goth, all of it!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mCHUw7ACS8o

On the Derleth rewrite – my own experience suggests it’s unlikely that Everil Worrell wasn’t consulted, though I don’t know for certain. When he bought my first tale back in 1962 he made it a condition of the offer that I authorised him to rewrite it as necessary (which, unlike the Worrell, it needed). Or might he have bought reprint rights direct from Weird Tales and not involved her? Maybe the answer is in his papers somewhere.

I was so confused by the summary and then Anne’s references to some other version that wasn’t summarized as if we were supposed to be familiar with it.

And I am gratified to know that I am correct in hating August Derleth. Am rewriting another of his stories right now.

Iris, I’m sorry you hate my old friend August. Like the rest of us, he was a complicated flawed creature, but my field would be much poorer without him and Arkham House (and I might never have had a career as a writer).

Ramsey, if he helped you in some way, that redeems him considerably in my eyes. I love your stories.

I actually only really dislike him because of one scene toward the end of The Shuttered Room, when the frog monster is burning alive and cries for its mother. It felt too mean and too terrible, and it’s upset me ever since.

You’re right about Arkham House, too.

Well, thank you very much, Iris! I’ve always taken the monster crying out for its mother in “The Shuttered Room” to be his version of Wilbur Whateley’s brother calling out for its father.

As for me, though, August took me on and gave me crucial editorial help at the start of my career, and published my first books. Our ten-year correspondence is collected in a book from PS Publishing.

But think of the motivation! Whateley’s monstrous brother is sort of SUMMONING his God of a father, right? It’s a moment of power. Derleth’s version is a baby, on fire, who watched the only person who ever loved it starve to death, and it misses her.

I will absolutely look up this book, though, correspondence is my favorite kind of memoir.

@anne: Ooh, I didn’t know river herring ever ventured so far up the Hudson. Cool! I’m rather interested in those little doobers, having written an extensive fact sheet about them (alewives, that is) in college.